Crossing the River: Artist Interview with Valerie Boyer

We’re taught in school about Ohio’s role as a free state, but what were the experiences of those who risked their lives to reach our borders? What happened once they made it to the river?

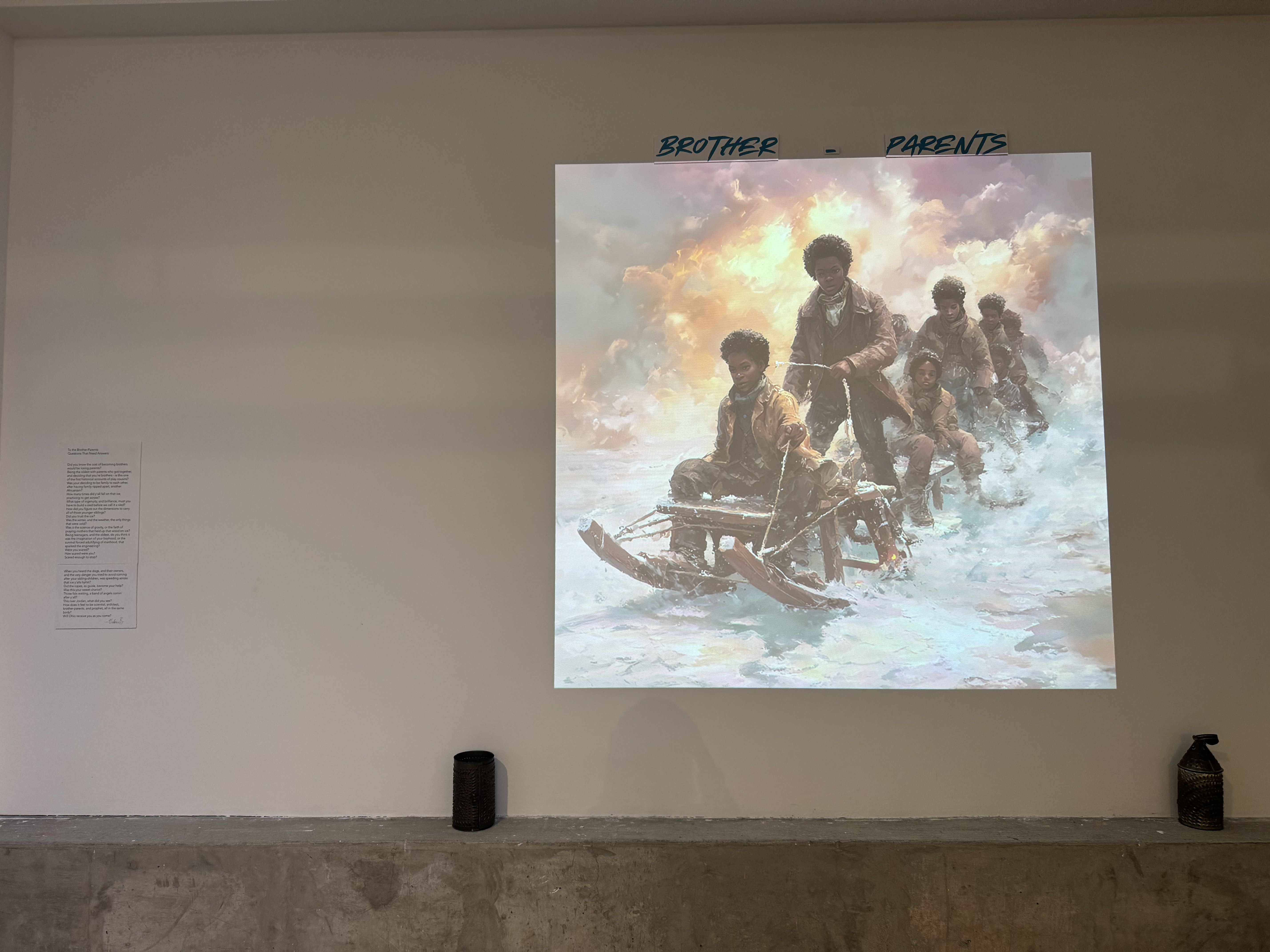

These are the ideas that Valerie Boyer sets out to explore in her poetry and installation. Valerie’s work is currently on display in the lower gallery of Urban Art Space in downtown Columbus as part of I Know Why the Blackbird Sings, a show in collaboration with Community Artist-in-Residence Tyiesha Radford Shorts—on view through September 27.

The title of this show—I Know Why the Blackbird Sings—is a reference to Maya Angelou. How did her work or that of other authors impact your writing for this exhibition? How did you approach the creative process?

The work of Maya Angelou, Renita Weems, Angela Davis, Octavia Butler, Zora Neale Hurston, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Francis Ellen Watkins Harper, Gwendolyn Brooks, Brittany Cooper, alongside so many others, are constantly weaving through my writing, my vision-casting, my creating, my research, and pretty much every essence of existing in this body. It is impossible not to feel a call to the constant imagining and remembering of Black life, through Black bodies.

My approach to this process was born out of my research as a historian and artist. I have a concentration with nineteenth- and twentieth-century African American history, but currently I am OBSESSED with the Ohio River. More often than not, the Ohio story of the Black experience as a “free” state, and a stop on the Underground Railroad Network, is told from a Eurocentric lens of revisionist redemptive history, and more often than not, the barbaric nature of the treatment of Black folx here is covered and/or buried. But the Ohio River? It is constantly explaining and exposing that “life ain’t been no crystal stair.”

There is a foundation and reconciliation that comes with being able to give people histories, a beginning, and treasures that were intentionally kept from them, and Ohio River is doing just that.

In addition to working at the Ohio History Connection and founding the Rebecca Owinale Foundation, you’ve spent time in the classroom as an instructor. How has teaching impacted the stories you tell through your art?

I am the daughter of generational educators, and went to Howard University, with one of my minors being education. A huge part of HBCU culture is teaching what we call “edutainment” and “artivism”. As an educator, it is ingrained in your very being that you are responsible for both, as you are a part of the less than 7% your students may ever see. Art within education is not optional. It is just as much a part of the pedagogy as the curriculum content is itself. Because of the rearing and modeling of my own family, I’ve never known them to be optional separate entities. Everywhere I go is a classroom. The how may change, but the call? The edutainment and artivism of it all? That’s forever.

Within your poem “To the Brother Parents: Questions That Need Answers,” you pose many questions to the reader. What inspired you to adopt this format?

I’ll be blunt. I struggled with this poem initially, because I didn’t know how to communicate this story! I didn’t know if it was supposed to be a prose, just the historical primary document itself, the poem, or what. For a while there, I stepped away from the writing, and just sat with the story itself. In my reading and rereading of the account, with the limited documentation we have, I found myself in conversation with the brothers and was left with all of these questions. From there, I immediately realized that the questions I was asking them, about family, creativity and ingenuity before its time, the intersection of theological conundrums, creating chosen family, growing up before your time, and every question that came after, are still questions Black folx are consistently having to ask themselves today.

One of my favorite things about some of the authors I named who wrote fiction is that their stories often have no concrete ending. They leave the reader to finish the story for themselves and the world around them. In inviting people to have this ancestral conversation with these brothers, I was also inviting us to have the conversation with ourselves.

As visitors come to the gallery, what do you hope they will take away from their experience at the show?

A deep love, and reverence, for the water—as this place God, ancestor, and Black folx seem to have the most sacred relationship with.

A wrestle with the memory of what it means to exist in a place that is supposed to be free, only to get there and find it still wasn’t.

A call to remember the brilliance that emerges in survival, and resistance, of history, and inspiration to see it as prophecy of who we’ve always been and will always be.

An invitation to pivot from the plan and make some the wrongs right.

A conviction the continue to tell whole stories, not as revised and redeemed, but as full, complicated, beautiful, and whole.