Let the Ghosts Chit Chat: An Artist Interview with Keya Crenshaw

Multidisciplinary artist Keya Crenshaw is a native of Columbus, Ohio. Keya is the founder of Black Chick Media, LLC and the Scared Spaces Collective. Keya’s work, Cypress, Camellias, Magnolias, and Red Clay: Ancestors on the Wall, Let the Ghosts Chit Chat, explores the house our grandmothers built, where we are reminded that home is never just a place, but a chorus of memory, love, and presence that continues to shape us.

This installation is part of a larger show, Don’t Sell Grandma’s House, along with other works by Matthew Pitts, Sharbreon Plummer, and Marshall Shorts. This exhibition can be found in the upper gallery of Urban Arts Space through September 27, 2025, alongside I Know Why the Blackbird Sings in the lower gallery. Both shows were curated by Urban Arts Space Community Artist-in-Residence Tyiesha Radford Shorts.

What family memories inspired the creation of Cypress, Camellias, Magnolias, and Red Clay Ancestors on the Wall, Let the Ghosts Chit Chat?

This work is rooted in the memories of both of my grandmothers’ homes, as well as my great-grandparents’; spaces that were more than shelter—they were sanctuaries of love, culture, and continuity. They hosted and held holidays, birthdays, and all manners of moments both joyous and grief filled. All homes were filled with music, food, and photographs that watched over us like protectors.

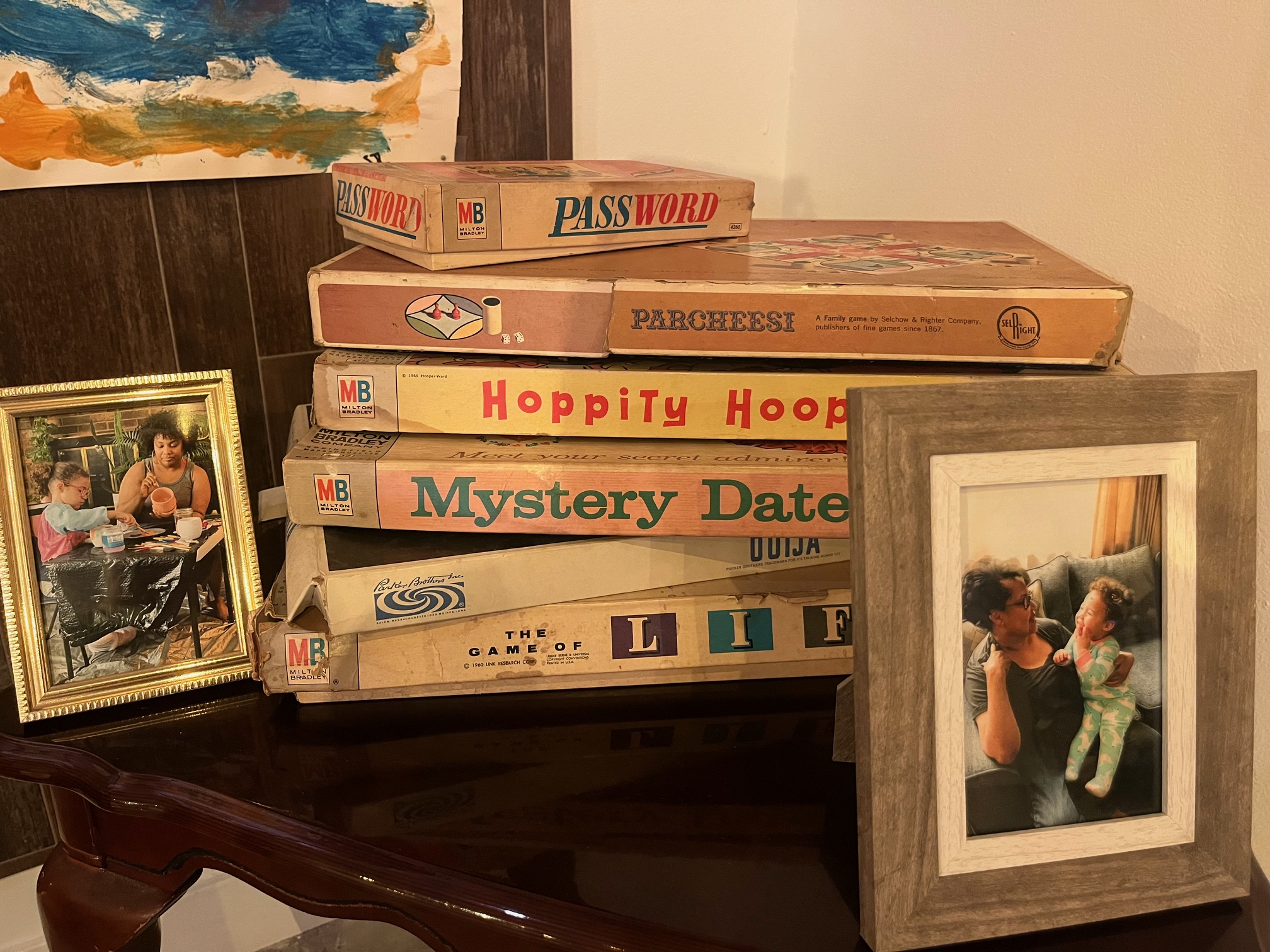

I vividly remember homes full of stories told around kitchen tables and in living rooms, spending time with my grandfathers as they listened to Miles Davis on vinyl or tended to the garden, and watching my grandmothers bake cakes and braid my hair. The objects I have chosen—heirlooms, furniture, photos, even something as small as a peppermint bowl—all come from those houses. They remind me that a home is not defined by walls, but by the presence of family, memory, and the echoes of our ancestors. I have always believed that your foundational tribe helps shape who you are and who you will become.

The effects of redlining and dispossession are central themes to the larger show, Don’t Sell Grandma’s House. How do these themes inform your artwork?

Redlining and dispossession are not abstract concepts in most Black families' stories—they are lived realities. The fear of losing the family home has always been present, whether through predatory lending, gentrification, or simple economic vulnerability. For example, a medical center that bought a hospital near one of my grandparents' homes continuously offered to buy the property, under value, of course, but my grandmother held strong. She and my grandfather had paid the home off decades before, and, as a duplex, they always wanted the family to have a space to live if needed. So, they stood firm and did not budge, but that presence was always a threat to homeownership as the medical center was swiftly buying other homes in the neighborhood.

That said, for me, by recreating a foyer—a space of arrival, of gathering, of welcome—I am asking viewers to sit with what is at stake when these homes are lost. When a house disappears, we do not just lose property; we lose archives of love, care, and culture. My work honors the resilience of Black families who continue to hold on, even when systems are designed to push us out.

Music plays a large part in your art, as seen by the old-school Victrola on display. What role does music have within your family and personal history?

Music is the soundtrack of memory in my family. I remember records always spinning, 8-tracks and cassettes playing. The constant presence of church hymns was always buzzing in the space, whether hummed, sung, or simply the ghost of a song without the actual music, and soul and jazz classics carried us through joy and hardship alike. For me, the Victrola is more than an object—it’s an altar to that tradition. Jazz, blues, and gospel, are the voices of ancestors, a way of keeping time with their footsteps. Music reminds me that healing and celebration often arrive in the same song.

Listen to the artist's exhibition playlist here.

Your installation consists of two components, with one section featuring family photos and the other children’s paintings. What was your process for creating and curating these gallery walls?

When Tyiesha asked me to be a part of the show and told me the theme, I instantly panicked. I had so many ideas about how I could interpret and share the space, but I couldn’t decide what that meant or looked like; then, I focused on the feelings, recalled memories, and spoke with family. The idea of family photos came first—a lineage on the wall that grounds the installation in history and ancestry. The children’s paintings are from my niece—she made them in her grandmother’s, my mother’s, home.

I wanted to show that love and pride grandparents have for their grandchildren. They would gladly display any and everything you created or accomplished. I wanted to bring in the voices of the present and future, a reminder that the home is never static; it evolves as new generations enter it. Together, these two walls are in conversation. The photos remind us where we come from, and the children’s art imagines what’s yet to come. Curating them side by side was my way of showing that a house is both memory and possibility.

Nature is seen throughout your installation, including the wood furniture and houseplants. How did this idea of nature inspire this work?

Nature has a tendency to be present in the Southern Black home. Cypress trees, magnolias, red clay—these aren’t just backdrops, they are kin. My grandmothers always kept plants inside their homes, as if to blur the line between inside and outside, between survival and beauty. In New Orleans, my great grandparents, great uncle, and grandmother lived on Magnolia Street near Tulane University. My great grandmother, who was part Choctaw Nation, always kept a bounty of snake plants on her porch. In both African folklore and Indigenous mythology, snake plants represent strength, protection, and good fortune, and its sharp leaves are believed to ward off negative energy. So, even before you entered, you knew this was a protected home full of love and prosperity.

I have carried on this sacred and loving tradition as I have well over forty house plants (and counting!). One of my earliest and fondest memories is when I would help my grandmothers take care of their plants. Pruning, watering, feeding—they were such nurturing acts of love and care, and I am honored to be called to carry this act forward.

The wood furniture was also an ever-present piece. Not only was it the furniture of the time—well before modern plastic and recycled materials—but it was made well and lasted decades. The wood and greenery root this installation in the natural world, reminding us that our homes are not separate from the land, but grown out of it.

If you could see the ghosts of your ancestors, how would you imagine they would interact with this space?

I actually asked myself this question repeatedly during the process of activating my space. Then, during opening night I asked my parents if they felt my grandparents and other relatives would be proud of this space. Luckily, my parents love and support me very much so the answer was a resounding yes, but it was really a foundational concept that my ancestors, should they walk this entryway, truly feel at home. For example, I pictured how my grandmothers honored family, both living and no longer alive, by filling the space with photos and items like crochet blankets and handmade quilts. I thought of my grandfather listening to jazz while having a whisky.

I remembered how my grandfather and grandmother would sit in the living room together welcoming family, discussing the Bible, or simply just sharing quiet space. So, I imagine they would feel at ease here, as if they had walked back into a familiar foyer. They might nod at the photos on the wall, hum along with the record spinning, sit down in one of the chairs as if to rest after a long journey. I believe they would recognize this as a space made for them—a place to linger, to watch over us, and to be remembered with tenderness. I have an ancestral altar in my home dedicated to them, and I’d like to think of this as a large-scale manifestation of that space.

What were the biggest challenges in recreating a space that felt like home to you?

Oh wow, so many! Sourcing pieces was difficult. I had a few key pieces in my own home, but I needed to connect with other family members in order to borrow and use items they had in their possession. Although, the biggest challenge was translating intimacy—very intimate memories and feelings—into a public setting. A grandmother’s foyer is such a personal, sacred space—it holds secrets, smells, textures, and sounds that are hard to replicate in a gallery. Every object had to carry weight and intention, so that even if a viewer has never stepped into my grandmother’s homes, they might recognize the spirit of their own caregivers or loved ones.

Did the creation of this installation change the ideas of what family and home mean to you?

I don’t think so, as I have always felt that “home” is less about geography and more about continuity. About a feeling that is indescribable but also rooted in love. It’s not just “this side of my family is from Louisiana,” or “that side of my family is from Alabama,” but the way those places meet inside me. Home is also not frozen in the past—it lives in the objects, rituals, and even in the children’s artwork that reimagines the space and brings it to life. Likewise, my definition of family has always included ancestors, neighbors, family friends, and even the ghosts that walk with us, reminding us that love outlasts time. I unlocked so many long-forgotten memories during this process that I am convinced my tribe was working through me.