Flesh, Skin, and Bones: Contemplating “A Love Letter”

“The wind opens up these wounds, and it hurts to write these words to you. But I know I have to tell you these truths in this way, understand?” — Tanya Diaz-Kozlowski

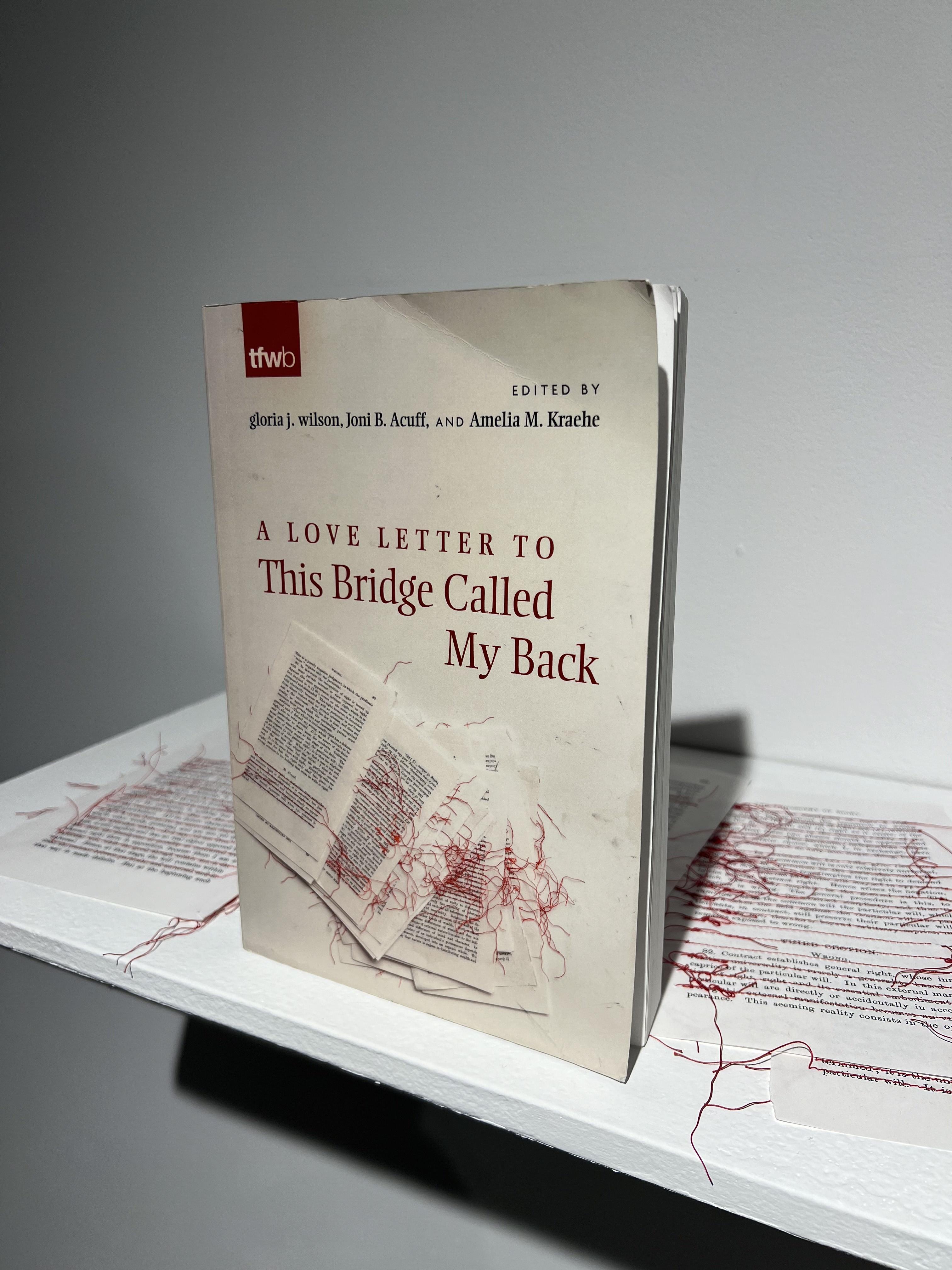

What do trauma and love have in common? Both leave a lasting impact—one that changes who you are forever. In “Flesh, Skin, and Bones,” Tanya Diaz-Kozlowski reflects on her traumatic experiences framed within a love letter. She writes about her life as a Chicana lesbian and compares it to trying to untangle yarn, but instead of untangling, it just becomes more intertwined. Found within the anthology A Love Letter to This Bridge Called My Back, Diaz-Kozlowski’s work and many others inspired the associated exhibition now on display at Urban Arts Space through June 29, 2024.

Diaz-Kozlowski’s accounts are brief but raw. Every word is intentional and has a heavy story behind it. “Religion. Recovering Catholic.” Those three words brought to mind dozens of my own complex feelings toward religion as an ex-Catholic myself. In that moment, I felt the yarns of our stories entangle, if only for a moment.

Within her letter, she includes italicized poetic asides, which seem to be her innermost thoughts—chaotic, dispersed, and a bit melancholy. The letter itself is vague, the poetry within it visceral. In this way, Diaz-Kozlowski powerfully presents her inner turmoil, using these asides to process her pain while simultaneously trying to present it to the world.

As I made my way through the Love Letter exhibition, I found this theme of pain prominent among the various works on display. The pain is intergenerational and systemic, just like Diaz-Kozlowski’s. The work Invisible Identity: Mujeres Dominicanas en California, delves into this idea. Spotlighting her immigrant grandmother and the rest of her family, Dr. Sonia BasSheva Mañjon shares their experiences in a new country. By the third generation, they are fully assimilated into America, but they lost parts of their own culture and identity in the process.

Like the pieces in the Love Letter exhibition, Diaz-Kozlowski portrays her desperate desire to be known, to be loved, to be seen as all of herself. In her essay, she finds this in another queer woman: “Your eyes sunk into mine, held me. How did you see me? I let you.” She is not used to being vulnerable. Yet through a detailed moment of intimacy, she shows herself opening to someone else who is like her. She is inviting not only the letter’s recipient into this moment, but all of us.

***

“Flesh, Skin, and Bones” ends with an expression of rage. Rage that stems from generations of abuse that not only she suffered, but other marginalized people as well. Diaz-Kozlowski shares a story that is so personal yet sadly relatable to so many. As a Latina queer woman, I too have felt rage at the injustices and abuse many of my sisters have faced. The rage builds and builds, and writing gives Diaz-Kozlowski—and all women—a way to take our power back.

Writing is not the only way to do this, though. Rage was expressed throughout the exhibition, with one piece in particular standing out. This was Cute Rage Press Sticker Sheets by Aram Han Sifuentes. Here, Sifuentes takes her rage and makes it known, calling out oppressive tactics and systems. While both creatives share anger, it was interesting to note the different ways each woman processed it: one through a public display and the other through a private letter.

Shifting from desire to the equally strong emotion of rage illustrates the tumultuous nature of Diaz-Kozlowski’s experiences. Healing is not linear. Diaz Kozlowski confides to her love about “the night terrors, the sleepwalking, the pain,” highlighting how love allows her to break down trauma but also forces her to relive it.

This short essay opened the door to Diaz-Kozlowski’s life. At times, it was more like a mirror than a door. Her musings on love and rage as a queer woman of color bring out experiences and emotions that are common among people who share these identities. And through it all, she addresses a woman she once loved, a steadiness among the rocking waves of her life.

Diaz-Kozlowski’s experiences reminded me of my own phases of growing up. Love and rage came in abundance for me as well. The personal and systemic intertwined: love for a woman but anger at having to hide it from the world, love for my family but anger at what their religious beliefs put me through. Every piece in the exhibition reflected something deeply personal about the artists’ lives that connected more widely to the issues women of color face. There is community found in suffering shared pain, and I felt how the artists of the exhibition—as well as Diaz-Kozlowski herself—invited me into that community today.