Portable Paradise: A Confluence of Poetry and Art

A loud murmuring runs through the gallery; voices from one end of the space travel up to the ears of those walking down the lucent corridor. As visitors enter, they are greeted by dozens of people mingling, eating, and taking in the variety of works: sculptures, paintings, photographs, and poems.

Visitors find their way to their seats, and as the time moves towards 7:30 PM, the murmuring softens and anticipation amongst the crowd feels palpable. The lower gallery is filled with rows and rows of chairs, with the crowd becoming so large that visitors overflow into the back and stand to get a good view of the stage at the far back of the lower gallery.

“Formation” by Beyoncé swells throughout the space, and a woman takes the stage. She cannot be missed, her green dress so vibrant that its color illuminates off the lights, making it shine from across the gallery. This is poet and curator Ajanaé Dawkins, Urban Arts Space’s current Community Artist-in-Residence, who introduces the exhibition that surrounds her: Portable Paradise.

The title of the exhibition is taken from a poem of the same name by Roger Robinson, a Trinidadian and English poet whom Urban Arts Space was lucky enough to host as the headliner of the poetry celebration, in which he read “A Portable Paradise,” along with some of his other works:

And if I speak of Paradise,

then I’m speaking of my grandmother

who told me to carry it always

on my person, concealed, so

no one else would know but me

Robinson implies in “A Portable Paradise” that everyone holds their own unique idea of what paradise looks like to them and that they must cherish that conception because they exist in an environment that is actively trying to steal paradise away from marginalized groups. Within the poem are themes of family ties, fighting against marginalization, and personhood.

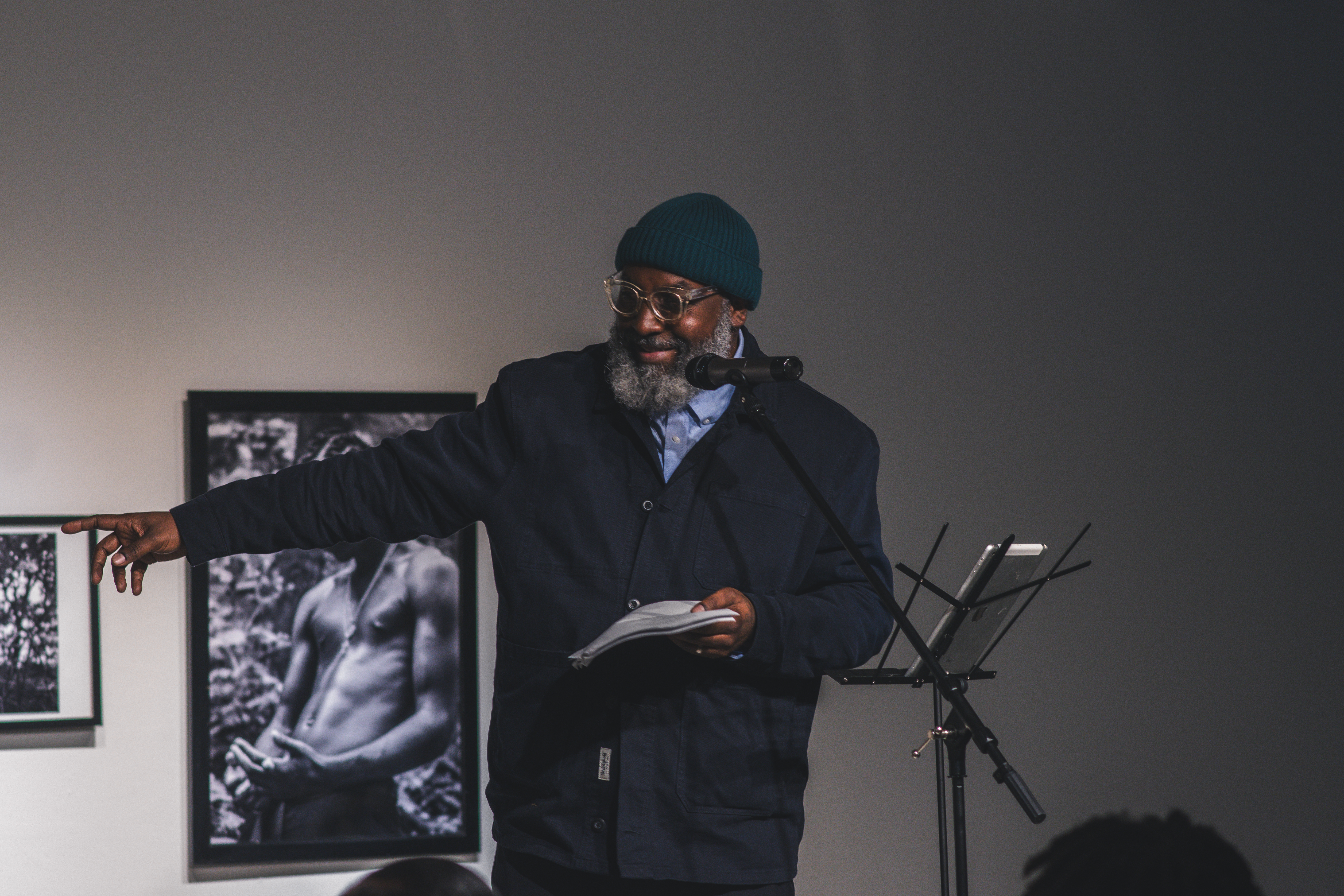

Roger Robinson was born in Hackney, U.K. but moved to Trinidad at four years old, and then at nineteen, he moved back to the U.K. Robinson writes about his lived experience as a Black man in both Trinidad and the United Kingdom. Robinson’s presence captivates the entire audience, his rich voice traveling throughout the crowd as he asks everyone to proclaim “hooray!” every time he reads a poem chosen by Peter Kahn, a spoken word educator and one of the poetry celebration coordinators.

“Story”

If your body isn’t telling your story it means someone else is using your body to tell theirs. And you better solve that problem.

“Grace”

And I think if by some chance I am not here and my son’s life should flicker, then Grace. She should be the one

Before the headlining poets, the event hosted student and faculty poets from various high schools and colleges in the Columbus area. The performers read poems about everything from ukuleles to a grandmother’s lipsticks.

Another headliner alongside Roger Robinson was Cynthia Amoah, a Ghanaian American poet, performer, and teaching artist. Based in Columbus, her work reflects on her ancestry, traditions, and culture, transcending labels and embracing her multifaceted identity.

And if I write the things I speak, what truth will rise from my bones

Amoah’s commanding voice took control of the audience, and every listener was glued to her performance as she transitioned into her final poem.

My mother lives through disaster, like a missile fire burning so fierce in her eyes. My mother every day says this too is a beginning—you can start here.

The third headliner, Ajanaé Dawkins, is a poet, performer, educator, and theologian. She uses her maternal family as a vessel to examine a variety of themes, including grief, politics, justice, and faith. One poem she read was entitled “When Viola Davis Won,” which she prefaced was a poem she has been meaning to retire for the past handful of years, but she’s noticed it has been so powerful and loved by her audiences that she is unable to stop performing it just yet.

When Viola won, I thought about all the hunting they’ve done. How black girls we been prey. I saw her on that stage and swore there was a rifle in her mouth that I watched her blow the bullets back and suck them out one by one

Dawkins’s second poem tells the story of her aunt who had been missing for decades when her family discovered she had been murdered. It was her aunt who told her as a child that Black girls were from Mars, inspiring the poem.

They were dislocating the grammar of my hair into three parts of speech until language flowed down my back. Until I was milk-carton-photo ready.

Along with the highlighted poets, the work that lines the gallery fits into the themes of Portable Paradise in their own individual ways. The pieces describe paradise through lenses of faith, marginalization, nostalgia, family, and personhood. The paintings, sculptures, videos, and photographs in the space all harmonize with the night’s poetry.

What if by Laurie VanBalen describes paradise as the hope and search for safety amongst immigrants, in which that idea of paradise is stripped away from them when their families are separated at the border. Megan Reynold’s piece explores nostalgia as their form of paradise in I’ll Take You Everywhere, If You’ll Let Me. Paradise is a place of unquestioned and undeniable creativity, a place of escape from the white-dominated world for Travis McClerking in ByProducts of Proving Our Existence.

The pop-up exhibition, along with the poetry celebration, illustrates that paradise has a different meaning and connotation to every individual. Each artist and poet molded their meaning into a tangible piece of art—and we encourage you to do the same.