Reckoning with the Record Through Poetry with Urban Art Space’s Community Artist-in-Residence

In the fall of 2024, I had a fantastic opportunity to observe a workshop on conducting research and archiving history through poetry. I never considered myself a poet before, but this workshop introduced me to a whole community of writers and poets. This space allowed me to better grasp what it means to have a community in the arts that extends beyond the university. With our host's guidance, these writers cultivated a safe space for learning and healing as we navigated archiving and storytelling, which allowed us to create records that best echo ourselves and our communities. We don’t always have the “facts” because of barriers like colonialism, forced removal, and ethnocide that many communities historically face, but there are still experiences we know to be true.

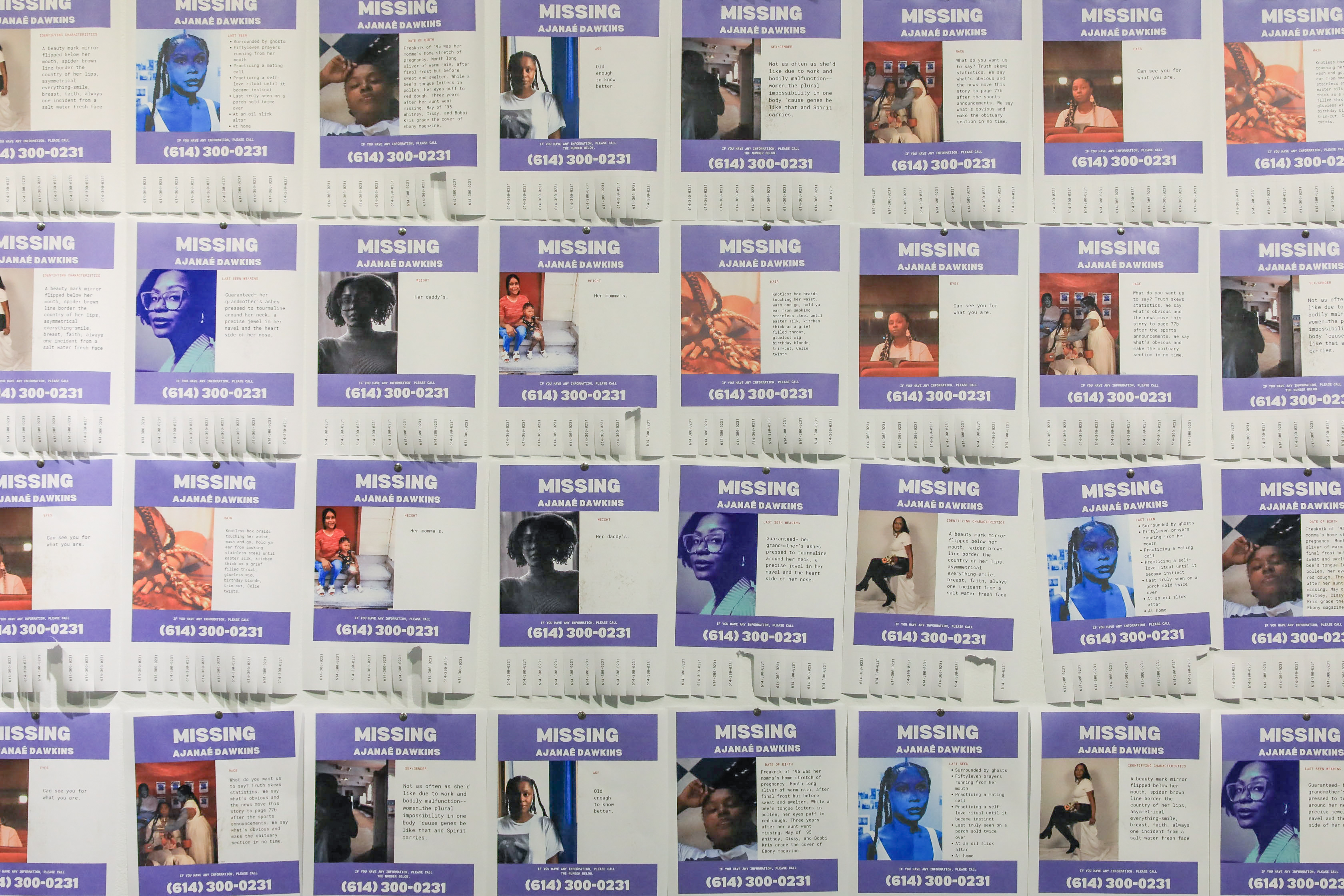

We often think of the documentary genre as being associated with film and photography, but poetry is a way of wielding text to trace, reflect, and question reality. The workshop, “Docu-poetics: Between the Stanza and Archive,” was led by Columbus-based poet Ajanaé Dawkins, who is Urban Arts Space’s 2024 Community Artist-in-Residence. Dawkins is an interdisciplinary poet, performance artist, and theologian. She has work published in the Indiana Review and Frontier Poetry, and is the author of Blood-flex which was the 2024 New Delta Review Chapbook Prize winner. She writes about the lived experiences of Black women to explore the politics of faith, grief, sisterhood, and sensuality.

Dawkins feels that workshops like this support her belief that education needs to be centered around access and giving resources to our community free of cost:

“I've gone into debt to get access to time, space, resources, and support so that I could flesh out my ideas and write in community... I created this workshop for independent artist-scholars who needed space to explore their research and artistic inquiries in community. I created this workshop because I need(ed) a workshop like this. ”

The workshop welcomed participants from all over the States and abroad, from Columbus to Chicago to LA and even as far as the UK. These participants were interested in engaging with various forms of research and archival practice through poetry. Our research spanned from tracing genealogy and writing memoirs to commentary on legislation as well as historical and current events.

We started the program by setting values like confidentiality regarding anyone's research and not doing anything that would cause anyone else harm. We were also given an independent research syllabus to help guide us. It was a living, breathing document that we could edit and change whenever, depending on our needs. Every week, we were expected to interact with the readings in the modules on Google Classroom and write two poems weekly, one during our weekly session and one outside.

Biases let us know our limitations, and boundaries hold us accountable.

In the first two weeks, we concentrated on ethics and biases when archiving. How we approach our work can shape our ethics, especially in memoir versus biography, telling our own stories versus others’. Confronting our bias early on will let us know our limitations by mapping out what we will focus on and not interact with. With my own project, I wanted to center on those most impacted by mass incarceration through everyday life, my life. Still, I didn’t want to focus solely on the arrests and deaths of incarcerated individuals, even though that was most of what I could find. The materials themselves also may hold bias, such as newspapers and court documents. Our bias can mean we will see things in materials that others may not. What do I know is missing from this material that others don't know, and how does that change the perception of this person or event?

This time was spent considering how our art practice required an ethics of rigor, meaning how we can be engaged with our ethics as much as we are with our craft. Ajanaé urged us to be responsible with our art:

“It is critical then to create rigorous ethics for how we work and what work we put into the world that considers those who would be impacted by our work now and those whose graves our work speaks over.”

We produced a list of things we hope our project will do regarding ethics. This helped me think about how I didn't want my project to be perceived. I didn’t want my project to play into the villainization of Black men with drug arrests nor to further frame Black mothers as failures. Then, we considered our boundaries and how to hold ourselves accountable to our ethics. This made me think about how I would honor the people in my research, specifically family members, and what permission I needed.

Alternative narratives are ways to fill in gaps.

As the sessions continued, we started to talk about limitations and where we saw absences in our research, whether because of systemic barriers or because we no longer had access to certain people. Many of us are dealing with ghosts, which can have spiritual implications. We consulted on navigating the gaps and how sometimes these gaps are a space for imagination and experimentation. How can alternative narratives even comfort us?

We read Concentrate by Courtney Faye Taylor, which is an archival poetry collection on the death of a fifteen-year-old Black person, Latasha Harlins, and meditates on Black girlhood. Taylor employs reviews of stores, all written by herself, and they become a series of poems. She tells about the neighborhood and how the hair stores were discriminatory and racist. Here, hermit crab poems were introduced—where a poem can take the form of recipes, obituaries, forensic reports, word searches, etc.—and then we were prompted to start our own. My grandmother spent most of her life in and out of hospitals. She always had a book of word searches in her hand when I visited her, and we would do them together. I played a lot with the idea of this as a poem and what would be going on in her head. Why word searches?

As independent researchers, we discussed what it means to ask each other for help in this space and when we are running into barriers, which I was, especially with getting interviews and not having access to certain documents. We considered the context of social politics when public records came together and how they might impact archives and our research. Ajanaé asked us to navigate this by writing down a list of questions that we felt we wouldn’t get answers to in our study. Then, we wrote about why there are gaps and asked ourselves whether those gaps are manufactured. We played more with counter-narratives to fill these gaps by creating a fictional character shaped by actual research details or facts. We could allow our character to tell a story shaped by authentic details of our archive through prose or a monologue. Ajanaé experiments with alternative narratives in her own work:

“Poetry gave me new ways to imagine and remember that I don't have to be loyal to standard practices. So what if my research becomes metaphysical and then comes back to reality? So what if I blur into futurism? If I confess and next to a news story? Like any genre or category, docu-poetics gave me language and tools that I would both use and break when they no longer served me.”

Setting intentions allows for deeper research.

The program ended with us sharing our intentions about our research and how we might all stay in touch. We thought about how our archiving can be about correcting or criticizing records. This led us to discuss the violence and erasure that is often seen in journalism, talking about editorial choices, what words are used that are racist concerning even headlines, and how they are beyond following “rules” about grammar and stylistic preferences. How might this look if different poets were in charge of headlines instead?

Ajanaé left us to ponder our research outside of these four weeks by asking us to write one intention for our study, one purpose for our writing, one intention for our community engagement, and one intention we have to care for ourselves through this process. I thought a lot about how I will continue to do this research in community as a way to not only be engaged but also care for myself as I am dealing with grief, injustice, and ghosts and exploring new ways to heal.

I walked away from this workshop with a new outlook on conducting research. This fantastic opportunity to work and collaborate with many talented poets showed me how powerful the practice of poetry is in archival and storytelling work. Conducting research through poetry allowed me to confront existing records about my own experiences and family history with incarceration and how I might better pay homage to the people impacted by it.

I now better understand what it means to set boundaries and abide by the ethics of the people you are writing about. This not only protects others but also aids in maintaining internal accountability. I learned what it means to use methodology, conduct independent research, and be in community with others. I am committed to furthering this research by considering what I feel obligated to do while protecting and respecting my mind and others.

A full list of Ajanaé Dawkins's residency projects, along with her exhibition archive, can be viewed here.